Some years I like to do something social for my birthday. When I turned forty, we rented an entire bar, and danced to funky tunes while drinking ‘chocolate cake’ cocktails. Some years I’d rather do something solitary; two years ago I spent my birthday diving on the big island. This year, I did something that […]

Some years I like to do something social for my birthday. When I turned forty, we rented an entire bar, and danced to funky tunes while drinking ‘chocolate cake’ cocktails.

Some years I’d rather do something solitary; two years ago I spent my birthday diving on the big island.

This year, I did something that wasn’t really exactly what I wanted to do for my 47th birthday; I buried my mother.

One of the things I shared with my mother was a profound dislike of nonsense. Thirteen years ago, she and I sat in a funeral parlor in Los Gatos California, and jokeed about the oddity of the process. The funeral director didn’t know how to react to us; he attempted to maintain an air of sympathetic dignity while we discussed using a cigar box to hold Ian’s ‘cremains’, luaghing at how it would have pissed him off because he hated smoking so much. The entire process struck us as odd and silly. Later that day, we had a similar conversation at a local cemetery, this time with someone who was able to acknowledge the oddness of his profession.

Some weeks later, we would stand on the grassy lawn of that cemetery interring my brothers ashes along with a rubber Bullwinkle.

The last funeral I attended was that of my father in law last spring; it was touching to see the outpouring of love and respect, and then later to hear ‘taps’ played while his casket was lowered into the ground. Yet he also misliked fuss and bother; the ceremony was for his wife. She’s an old-fashioned lady who likes things done correctly.

My mother wouldn’t have wanted that; she would have wanted to get it the hell over with; a feeling I share. So when I sat in those same seats a dozen years later, the answers were the same. No nonsense. Cremation. No casket. No funeral. Burial of the ashes only because we already had a plot. Just the cardboard box and the most basic bronze urn.

I joked about the cardboard box, and about caskets that look like furniture, and about the idea that dead bodies should be kept fresh. But no one laughed about it with me.

I choose the day I did – Friday November 28th – because it was a convenient day. It didn’t seem like a big deal to me.

Friday was an appropriately grim, cold gray day; I stood at noon shivering, on that same patch of grass that had taken my father’s body and my brother’s ashes, in the same cemetery where my grandparents lie side by side. Four below ground and five above; myself, my wife, my children, and my mother in law, the last living grandparent.

There was incense in the air from upwind, and the eerie skirl of bagpipes from down; burials with far more fuss and ceremony than ours. And as I waited for someone to bring out my mother’s ashes, the weight of death and sorrow struck me.

I hadn’t expected the rush of tears. I’d said my goodbye to my mother when I left her hospital room three weeks before; I’d let the tears come as much as they seemed to need to, and while the idea that she’s gone still shocks me now and then, I’d expected the same sort of dull ache of sadness that accompanied planting my brother.

I had to walk away; I grieve best in solitude.

After a bit, I wiped my eyes and came back; and with a quiet economy of motion, a groundskeeper brought out a small plastic box and removed the plywood and astro-turf lid from a shaft three feet deep in the clay. I wanted to tell my mother than she was going in the ground in something that looked like it should cool a six-pack.

I took the small metal urn, and placed it in the white casket. As when I stood alone with her in the hospital, waiting for her breathing to stop, I felt as if I should have something profound to say. That night, all that came to me was ‘goodbye, mom’.

This is where those who worship something have an advantage; they know what to say. I, though, had nothing but mute silence.

The groundskeeper took out a tube of super glue and fixed the lid in place, as if he were building some scale model of a casket. He carefully wrapped a strap around the box and lowered it into the earth, and then replaced the astroturf lid.

Five below, and five above. Now we’re even.

I could still smell incense; the bagpipes were gone. My family got into the car, and I took a walk. I tried to find my grandparents raves, feeling that somehow I needed to say hello to them, symbolically let them know their daughter now shared their address. But I took a wrong turn, and wound up in a row of child graves.

I’m come back later, I thought. You’re not going anywhere.

It was several long minutes, though, before I could pull myself together enough to get back in the car. As we drove to a nearby restaurant, Ruby quietly took my hand and held it.

Later that afternoon, we went back with flowers; red cyclamen for my family’s shared grave, white for my grandparents. My mother’s name is already on the small, flat stone; carved when the stone was set a dozen years ago. Too many names for so small a stone – Jack, Ian, and Greta. The plot is full now; but I don’t want my ashes in the ground in a suburban park in northern california. When I go, I’ve told my daughters, put what’s left in a sack with a weight and drop me down into the deepest ocean depths.

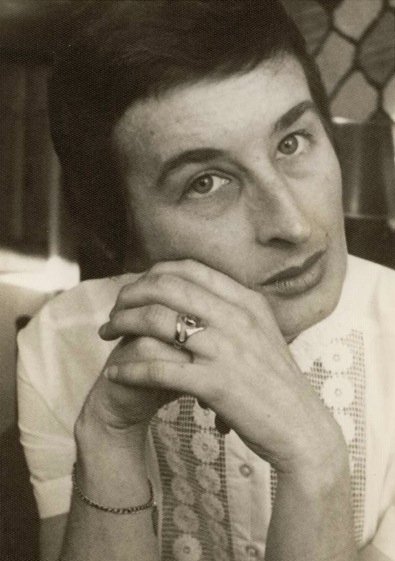

When I looked at my grandparents names, carved into red granite stones, it bothered me that my grandmother’s nickname – Cookie – wasn’t on the stone. Never once did I think of her, or address her – as her given name (Hazel). It bothered me also that her place of birth had been left off. My grandfather’s stone says ‘oklahoma’; hers should say ‘texas’. And I resolved to go back and fix it, and to fix my mother’s stone, which was done in haste. My mother wanted to be done with it, and hurried the choice without me. But the stone that is all that’s left of her life needs to say something about her, more than her name and the year of her birth.

The stones left to mark our graves will sit there a generation later. Strangers will stroll through the grass, looking for someone, or just looking. Grandchildren and great grandchildren, maybe, will look for a name they’ve seen on a family tree. That final marker should do more than just carry a name; it should say something about whomever it now represents.

It’s a silly thing, but markers mean something to me; before my next birthday, I need to fix that.